Projects / Fatma Sultan Mosque

Fatma Sultan Mosque as the Gümüşhanevî Tekke

In the year 1859, Fatma Sultan Mosque became the headquarters of the Ziyâiyye Branch of the Naqshbandi Khalidi Order represented by Sheikh Ahmed Ziyâeddin Gümüşhanevî. Gümüşhanevî continued his teaching and guidance activities in the cell at the Mahmut Pasha Madrasa. After the sheikhdom was situated in the Fatma Sultan Mosque by Gümüşhanevî, who had earlier, continued his teaching and guidance activities in the cell at the Mahmut Pasha Madrasa, the mosque simultaneously took on the identity of the tekke. In the middle of the 19th century, neglected and generally closed to [regular] worship, this mosque was restored by Ahmed Ziyâeddin Gümüşhanevî. One of Gümüşhânevî’s successors, Kastamonulu Hasan Hilmi Efendi, volunteered to undertake the duty of muezzin.9 In 1875, Gümüşhanevî had a sixteen-room house and a tekke built and donated as a waqf to this mosque, which was serving as the tevhidhane where the dervishes were running a hatm-i hacegân [ceremony to ease trouble or danger]. It is known that after the construction of the house and the tekke, Gümüşhanevî moved there and lived in that house, which was called the sheikh’s meşruthane [private quarters]. Thus, from this date, the mosque became known as the Gümüşhâneli Dergâh-ı Şerifi [the Gümüşhâneli Noble Lodge].10

Fatma Sultan Mosque as the Gümüşhanevî Tekke

The opening of the mosque took place on 24 October 1727 (8 Rabi' al-awwal 1140 H.) with the participation of Sultan Ahmed III and his Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha. The first sermon was given by Sheikh Yahya Efendi.2 The poet laureate of the period, Nedim, commemorated the mosque with praise in a poem of fourteen couplets in his divan. The last couplet of Nedim’s poem was recorded in the inscription above the [main] door of the mosque.3 Gifts were presented to those given responsibility in the mosque like the sheikh, the vaiz [preacher], the mütevelli [trustee], the kâtip [secretary], the imams and the muezzins. The number of people given presents shows that the mosque had a very comprehensive service staff. Although there is no precise information about the mosque’s dimensions and interior decoration, it is conjectured that it was richly decorated and in keeping with the architecture and art of the period.4

It seems probable that, when the Sublime Porte met with ruin in the Hocabaşı Conflagration that broke out in October 1775, the Fatma Sultan Mosque also suffered great damage from the fire. In the inscription written in nastaliq cursive above the main door of the mosque, it was made known that this mosque was restored by Mahmud II in 1827-8 (1243 H.) by the following phrases:

Fatıma Sultan’ın ihya etti ruhun Padişah, [The Padishah has restored the spirit of Fatma Sultan]

Buldu eski revnakını bu ma’bed-i zîbâ yine, [This eternal beauty has found its former splendor again]

Harf-i cevherdâr ile İzzet dedim tarihini, [I have told its history with bejeweled letters and honor]

Etti Sultan cami’in Mahmud Han ihya yine.5 [Mahmud Khan has restored the [Fatma] Sultan Mosque again]

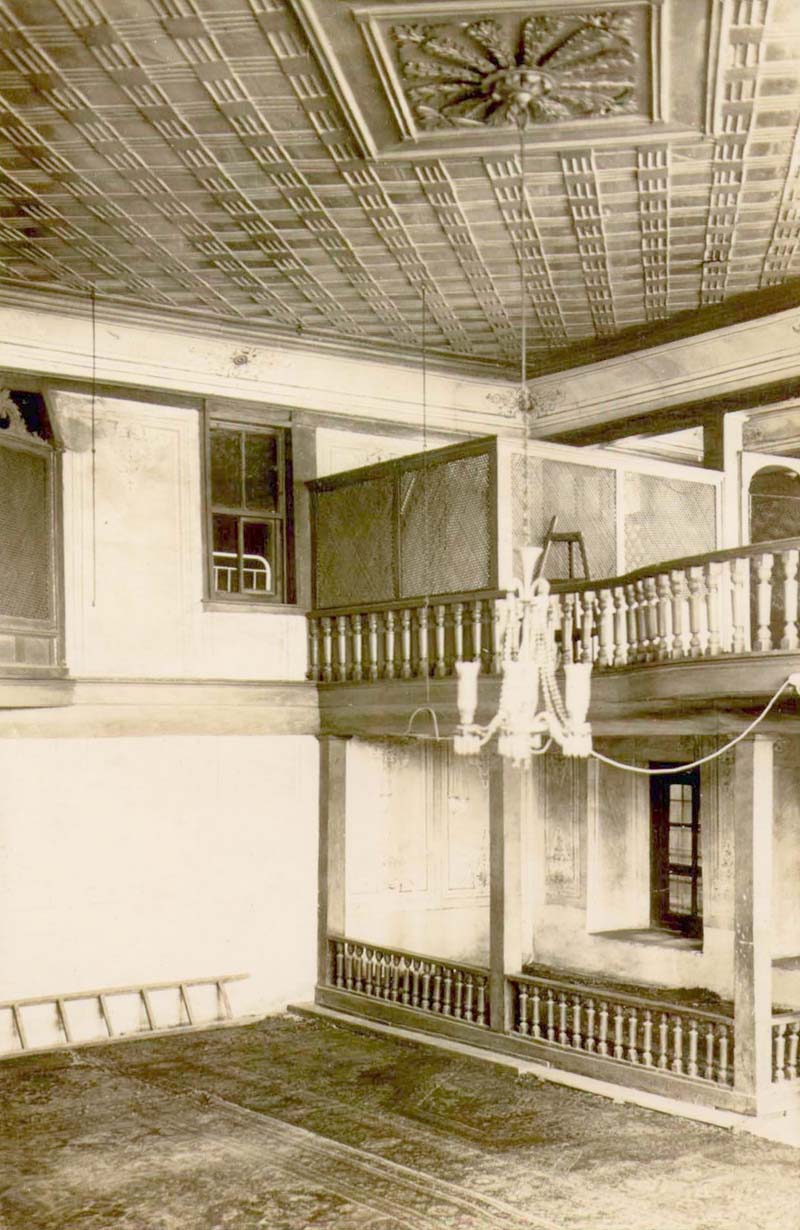

If we present some information about the construction of the mosque, the eastern section of the site was arranged as a mosque tevhidhane, the western section as what are called harem and selamlık [a women’s reception hall and a men’s reception hall], i.e., a meşruthane [private quarters/hall], and the sections of the tekke. For both parts, there are separate entrances and different courtyards. In other words, there is a mosque courtyard found on the eastern side and used by the congregation of the mosque. On the western side, there is a courtyard used by the residents of the tekke (the sheikh, his family and the [other] resident murids), as well as their guests. Tanman has stated, “On the southern side (qibla) of the mosque courtyard, is the mosque tevhidhane, on the western side, the harem building is located next to the mosque tevhidhane, and on the southwestern corner stands the minaret.6

In the courtyard, there is a fountain for ablution, and lean to the courtyard wall, there are toilets. Inside the mosque, there is a royal loge, the addition of which was thought of during the time that Sultan Mahmud II had the mosque restored (1827-8). There is an extremely plain minbar and a mihrab [a qibla niche].7 There is also a minaret of cut stone, just as Mahmud II had it made, which is known to be in the style of the 19th century minarets. The mosque is covered by a wooden roof with tiles.”8

In the year 1859, Fatma Sultan Mosque became the headquarters of the Ziyâiyye Branch of the Naqshbandi Khalidi Order represented by Sheikh Ahmed Ziyâeddin Gümüşhanevî. Gümüşhanevî continued his teaching and guidance activities in the cell at the Mahmut Pasha Madrasa. After the sheikhdom was situated in the Fatma Sultan Mosque by Gümüşhanevî, who had earlier, continued his teaching and guidance activities in the cell at the Mahmut Pasha Madrasa, the mosque simultaneously took on the identity of the tekke. In the middle of the 19th century, neglected and generally closed to [regular] worship, this mosque was restored by Ahmed Ziyâeddin Gümüşhanevî. One of Gümüşhânevî’s successors, Kastamonulu Hasan Hilmi Efendi, volunteered to undertake the duty of muezzin.9 In 1875, Gümüşhanevî had a sixteen-room house and a tekke built and donated as a waqf to this mosque, which was serving as the tevhidhane where the dervishes were running a hatm-i hacegân [ceremony to ease trouble or danger]. It is known that after the construction of the house and the tekke, Gümüşhanevî moved there and lived in that house, which was called the sheikh’s meşruthane [private quarters]. Thus, from this date, the mosque became known as the Gümüşhâneli Dergâh-ı Şerifi [the Gümüşhâneli Noble Lodge].10

Following Ahmed Ziyâeddin Gümüşhanevî, his disciples, Kastamonulu Hasan Hilmi, Safranbolulu İsmail Necati, Dağıstanlı Ömer Ziyâeddin and Tekirdağlı Mustafa Feyzi, respectively succeeded him in the office of sheikh. In the period when Tekirdağlı Mustafa Feyzi occupied the post, in the wake of the law issued in 1925 for the closure of the tekkes and lodges, the activities of the Fatma Sultan Mosque, which had won renown as the Gümüşhanevî Lodge, were ended. The lodge building and the sheikh’s quarters were assigned to the gendarmes posted at the [Istanbul] governorate and were used as a barracks and clothing depot. In the 1950’s, despite the Fatma Sultan Mosque being among the mosques proposed for restoration by the Türkiye Anıtlar Derneği [Turkish Monuments Association], no project was submitted. In the years 1956-1957, during the demolitions carried in the name of development, Fatma Sultan Mosque and the nearby buildings were demolished within a few days, and other than “Gümüşhaneli Street,” no trace has been left. Another historic monument project has been proposed for the restoration of the mosque and the outbuildings by the Mahmud Es’ad Coşan Eğitim Kültür ve Yardımlaşma Vakfı [Mahmud Es’ad Coşan Education, Culture, Friendship and Charity Foundation].13

FOOTNOTES

1. M. Baha Tanman, “Gümüşhânevî Tekkesi’nin Tarihî ve Mimârî Özellikleri,” İlim ve Sanat, Mayıs-Temmuz 1998, p. 115.

2. Semavi Eyice, “İstanbul'un Kaybolan Eski Eserlerinden: Fatma Sultan Camii ve Gümüşhaneli Dergâhı,” İstanbul Üniversitesi İktisat Fakültesi Mecmuası, XLIII, Istanbul, 1987, p. 478.

3. Ayvansarâyî Hüseyîn Efendi, (Ali Sâtı’ Efendi, Süleymân Besim Efendi), Hadikatü’l-Cevâmi’ (İstanbul Camileri ve Diğer Dînî-Sivil Mi’mârî Yapılar), eds. Ahmed Nezih Galitekin, Istanbul: İşaret Yay., 2001, p. 213.

(Bu mısrâ’la Nedîmâ söyledi târih-i itmâmın [With this line has Nedim told the history of its completion]

Ne a’lâ câmi’ ihyâ itdi el-Hakk Fatma Sultân) [What a sublime mosque has the Truth (God) restored for Fatma Sultan!]

4. Eyice, “İstanbul'un Kaybolan Eski Eserlerinden: Fatma Sultan Camii ve Gümüşhaneli Dergâhı,” p. 478, 9.

5. Ibid., p. 481, 2. [The tughra (official signature) of Mahmud II has a place in the middle of the inscription, but after the Language Revolution of 1928, this tughra was covered with plaster.]

6. Tanman, “Gümüşhânevî Tekkesi’nin Tarihî ve Mimârî Özellikleri,” p. 118.

7. Ibid., p. 118.

8. Semavi Eyice, “Fatma Sultan Camii”, DİA, v. 12, Istanbul, 1995, p. 263-264.

9. Tanman, “Gümüşhânevî Tekkesi’nin Tarihî ve Mimârî Özellikleri”, p. 118.

10. İrfan Gündüz, Gümüşhânevî Ahmed Ziyâüddîn (K.S.) Hayatı-Eserleri-Tarîkat Anlayışı ve Hâlidiyye Tarîkatı, p. 55.

11. M. Zahid Kevserî, Altun Silsile, trans. Vehbi Şahinalp-M. Zahid Kalfagil, Istanbul: Divan Yay., 1982, p. 106.

12. Hüseyin Vassaf, Sefine-i Evliya, eds. Ali Yılmaz-Mehmet Akkuş, Istanbul: Seha Neşriyat, 1999, p. 343.

13. Eyice, “İstanbul'un Kaybolan Eski Eserlerinden: Fatma Sultan Camii ve Gümüşhaneli Dergâhı”, p. 482-483.